'Misty' review — a physical, musical, and comedic feat

Misty, written and performed by Arinzé Kene, arrives at The Shed after a critically acclaimed West End run. The show fuses poetry, absurdist comedy, and live music. It follows Kene’s process of writing a play and features scenes of the work at hand: a spoken word piece about a man who starts a fight on a London night bus.

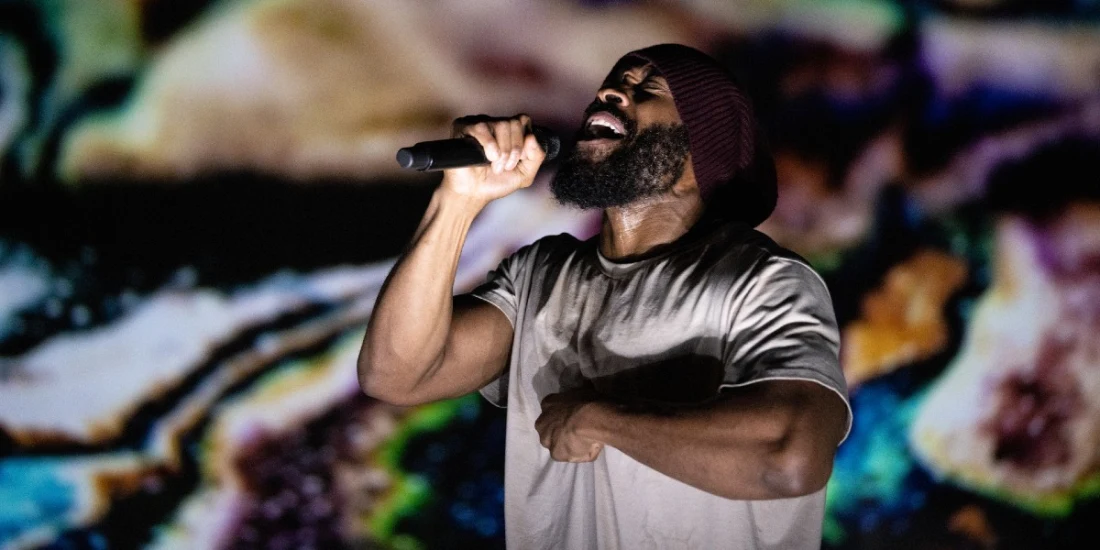

The opening number describes the city of London as a “city creature” and the man embroiled in the fight as a “virus.” He’s a victim of the gentrification happening as “blood cells” disrupt the urban landscape. Kene seamlessly transitions between playing himself and the “virus,” with a red knit beanie denoting the latter. He delivers the spoken word rhythmically with a clear, smooth East London accent.

Under Omar Elerian’s direction and Rachael Nanyonjo’s movement direction, Kene shines and redefines the solo show form. The performance is a physical, musical, and comedic feat involving running, jumping, and even simulated swimming. The show spotlights Kene, but he’s hardly alone on stage. The first-rate, integrated design envelops The Shed’s Griffin Theater and takes on a character of its own.

Video projections by Daniel Denton, lighting design by Jackie Shemesh, sound design by Elena Peña, and special effects by Jeremy Chernick all transform the set into a vibrant cityscape. There are a few scenes, though, where Kene’s spoken word drowns beneath the booming music and bright lights.

Rajha Shakiry’s sleek set is flanked by two musicians and the show’s co-music directors: Liam Godwin, an emphatic, head-banging pianist and conductor; and Nadine Lee, who impressively moves from the drums to the bass guitar throughout the show. The musicians also portray Kene’s friends Raymond and Donna, a couple unimpressed with Kene’s play within the play. Raymond says, “I mean, the whole ‘guy beats someone up on a night bus’ thing? It felt like another…” “Generic angry young Black man!” Donna interjects.

Kene’s character struggles to separate identity politics from his playmaking process. “I don’t even wanna write the enlightening play that ticks all the boxes and bridges the racial and sexual and LGBTQ+ abyss that some people expect of me. I just wanna write a play, man. A regular play. It’s really not that deep. Can a play from a person like me just be a fucking play already?”

The searing work grapples with cultural representation, gentrification, and the playful creation of art. Misty does so with many metaphors, most having to do with balloons. A standout scene features Kene in a wetsuit getting pummeled by water balloons. A stagehand throws them as Kene’s sister (portrayed by Ifeoluwa Adeniyi, a teen with a commanding presence) stands downstage at a mic and hurls insults about his writing. Another powerful scene includes a giant orange balloon that Kene is trapped inside, his head floating above it. While calling Raymond and Donna to defend his play, he attempts to escape the bubble. It's an impressive display of comedic timing and physical strength. (Both these scenes also display Kene’s bare chest — his abs elicited a few impressed gasps from the audience.)

Another scene includes a projection of a floating balloon, and another sees a cascade of orange balloons spill out of a giant box and dance along the footlights. Do they represent blood cells? Fleeting aspirations? Sky-high ideas? Orange-clad prisoners? Freedom? Death? All of the above?

The show runs two hours and includes an intermission, but after the tentpole water balloon scene closed out Act 1, several audience members looked around to see if the show was over. While Act 2 continues to follow both Kene’s story and the virus’s run from the “antiviral” police, it seems a bit, to continue with the balloon metaphor, inflated.

The play is open to interpretation, and there are some unanswered questions. The term “misty” might refer to the slang word for crack cocaine, or maybe it describes the nebulous, genre-bending plot or the smoggy smoke effects. Perhaps it refers to the misty-eyed Kene, taking a bow to conclude his tour de force performance. There are many ways to describe the show, and it reaches Kene’s objective: It doesn’t tick boxes of what a play about a Black man should look like, or what any play should look like, for that matter. Misty creates a new rubric.

Misty is at The Shed through April 2. Get Misty tickets on New York Theatre Guide.

Photo credit: Arinzé Kene in Misty. (Photo by Maria Baranova, courtesy of The Shed)

Originally published on