‘On Sugarland’ review — a dreamlike play about painful truths

Hollering is a recurring ritual in On Sugarland. Though wails of grief are certainly part of it, hollering is an act of mourning that overwhelms the whole body. As one character in Aleshea Harris's stirring and untethered new play puts it, a good holler starts in the toes and lives in the belly like a fist. It begins with the stomping of feet and often ends with someone passing out.

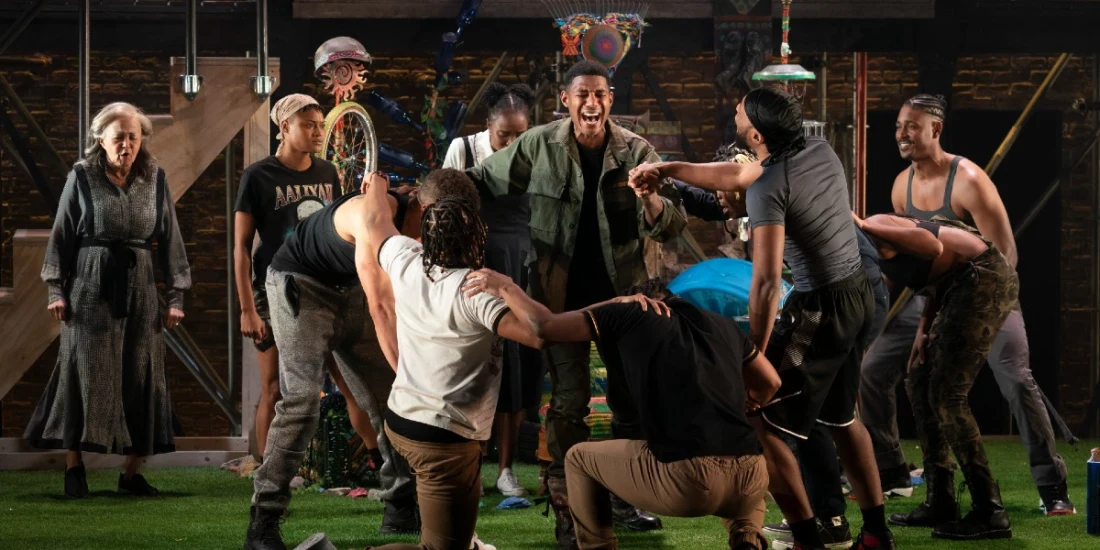

The funerary custom hits like a gut punch every time in this production from director Whitney White, punctuating Harris's dreamlike character studies with a collective electricity that exceeds language. There's a propulsive energy to these moments that sometimes goes missing in the interlocking portraits that surround them, of people circling the end of the road in a country at war.

Three one-room houses stand elevated side by side, above a circle of astroturf, ringed by railroad tracks (the set design is by Adam Rigg). On Sugarland refers to the makeshift plot out front where residents lay their loved ones to rest. The cosmic dead end often glares under hot lights, sunshine leaving nowhere to hide (lighting design is by Amith Chandrashaker). The scrapyard sculptures — a bike wheel affixed to a stool, cutlery, bric-a-brac — are what one cynic among them calls a "horrifying carnival graveyard."

The memorial's most recent addition, Iola, supposedly went missing in action. She's survived by her sister Odella (Adeola Role), who meditates even as she self-medicates with booze, and a 12-year-old daughter Sadie (KiKi Layne), now in her aunt's care. Sadie, who is mute to those around her but addresses the audience with a formidable grace, tells us she can raise the dead. Determined to uncover her mom's fate, Sadie asks her maternal ancestors; they don't have the answers, but Sadie recounts their warrior-like triumphs over racist fools in wonderfully vivid monologues.

A wounded vet (Billy Eugene Jones) acts like something of a pastor, leading the hollerings with soulful call and response. Despite his rotting foot, he longs to return to war, while his cadet son (Caleb Eberhardt), whom people call "special," is limited to patrolling Sugarland. The third house belongs to a pair of aging sisters, one who constantly tends the hallowed ground (Lizan Mitchell) and another (Stephanie Berry) who vigorously, and often hilariously, tends only to herself. A chorus, known as "The Rowdy" in the text, mill on the periphery, cajole, banter, and raise up the hollerings.

Layne is especially commanding as narrator and medium for the dead, conjuring whole worlds from descriptive orations and communicating volumes without words to the others on stage. Berry has the most cutting wit and wisdom to share, and she does so with flair and magnetic ease.

Harris spins a circular narrative, one that often loops back on itself like the cul-de-sac where it's set. The son shaves his father before the next hollering, urging him to sit still so he won't get cut. The vet philosophizes on the nature of war, speaking in veiled terms about what happened to him there. The vain sister preens in another too-nice outfit (costumes are by Qween Jean), while the other scoffs and scolds. Odella is always drunk, and Sadie still won't speak.

There's a reality to such repetition — what is a ritual but action on repeat? — and certain pleasures, too. (Berry rhapsodizes on ugly people's misfortunes to undiminished returns.) But the stalled quality to the lives on stage eventually makes its way into Harris' drama, which lacks an expansiveness and tension in its storytelling to fill 2 hours and 45 minutes.

Harris imagines a dramatic plane at once rooted in dirt and suspended in time and space, where it's possible to take a revealing, unfettered look at truths unmoored from their social contexts. That the provenance and logic of the war go unnamed is to the point — death will always come, and for Black people most urgently. Exhuming that foundational trauma, holding it up for audiences to feel, understand, and mourn, takes a daring and determined imagination that goes beyond words. It takes a hollering.

Photo credit: Lizan Mitchell, Charisma Glasper, KiKi Layne, Billy Eugene Jones, Shemar Yanick Jonas, and Xavier Scott Evans in On Sugarland. (Photo by Joan Marcus)

Originally published on