'Scene Partners' review — Dianne Wiest-led play brings cinema to the stage

Read our review of Scene Partners off Broadway, a world-premiere play starring Dianne Wiest and written by John J. Caswell, Jr., at Vineyard Theatre.

In 1985, nearly a decade after Jaws invented the modern blockbuster, the film industry staggered. Though hit movies like Back to the Future, The Goonies, and The Color Purple came out, the year was considered a clumsy step forward for the film industry. With the number of sequels going up and audiences going down, it looked like the film industry was about to turn its back on original storytelling. (Where have we heard death knells like this before?)

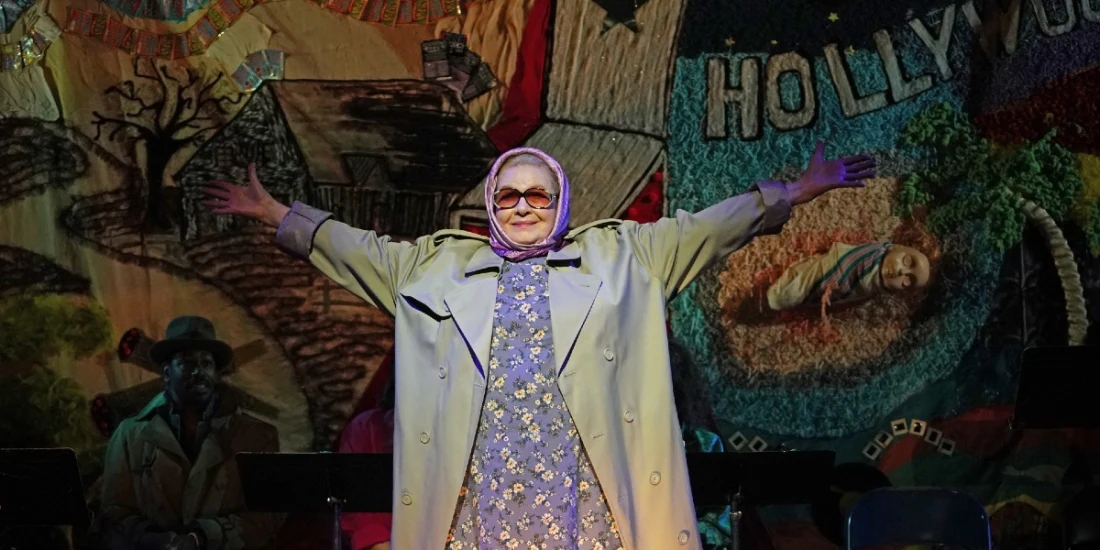

Also in 1985, in the new Off-Broadway play Scene Partners, 70something Meryl Kowalski (Dianne Wiest) decides to seek stardom in Hollywood. Her literal pest of a husband (we see him projected on a screen as a squashed fly) finally died, her daughter is a junkie, and Meryl is finally ready to be seen in all of her complexity. She travels to Los Angeles, has sex with a Soviet train conductor, acquires an agent (Josh Hamilton) at gunpoint, joins an acting class, and readies herself to unfurl her story. Or so Scene Partners wants you to think.

John J. Caswell, Jr.’s play is a bit of David Lynch, a bit of Requiem for a Dream, a bit of Black Swan, a bit of The Rehearsal, and a bit of John Cassavetes’s Opening Night for tasting. However theatrical the show is, the precarious nature of identity, and the power of film to expose, exploit, and isolate, appear to be Scene Partners’s primary concerns. The play surely hopes to bank on Wiest’s history as a screen star, from her appearances in Law & Order to her Oscar-winning roles in Hannah and Her Sisters and Bullets Over Broadway, attempting to create a meta-narrative about the blurred lines between actor, character, and the elusive notion of truth.

But it’s all kind of incoherent — narratively, structurally, tonally. There are moments of vicious black humor slammed against aspirationally terrifying drama, intentionally questionable accounts of trauma and abuse, and a kind of zany surrealism where planes of reality constantly shift.

Perhaps making sense of it all would be easier if the lead’s performance felt more grounded. Wiest is a legend, and there are glimmers of what makes her such, moments where the desperation to find a stable self amid the chaos feels real. But too often, she exhibits no strong persona for Scene Partners to destabilize. Tony Award-winning director Rachel Chavkin similarly cannot find an aesthetic throughline for the show, even with an overly generous helping of David Bengali’s projections.

It's unclear whether Scene Partners means to explore older women’s marginalization in Hollywood versus Hollywood's obsession with the artificiality of all performance and identity — or how the show wants to be in dialogue with cinema at all. Occasionally, it’ll meaningfully tap into one of the genres that seems to have shaped Meryl’s consciousness, like using the lights to create moody chiaroscuro and thrust her into a 1940s-esque noir. But for the most part, the show feels like a spool of film running through nothing in particular.

Photo credit: Dianne Wiest in Scene Partners. (Photo by Carol Rosegg)

Originally published on