'Tambo & Bones' review — making money, but shortchanging the audience

"It's quite easy to write poorly and have a white person call you powerful," Tambo & Bones playwright, Dave Harris, details in an essay in the play's program. The new production, now open at Playwrights Horizons, proves his point perfectly. The three-act, 90-minute production, directed by Taylor Reynolds, is part minstrel act, part underground rap spectacle, part academic hoopla that throws racial tomfoolery and the n-word in the face of a mostly white audience who take the bait and call it brilliance.

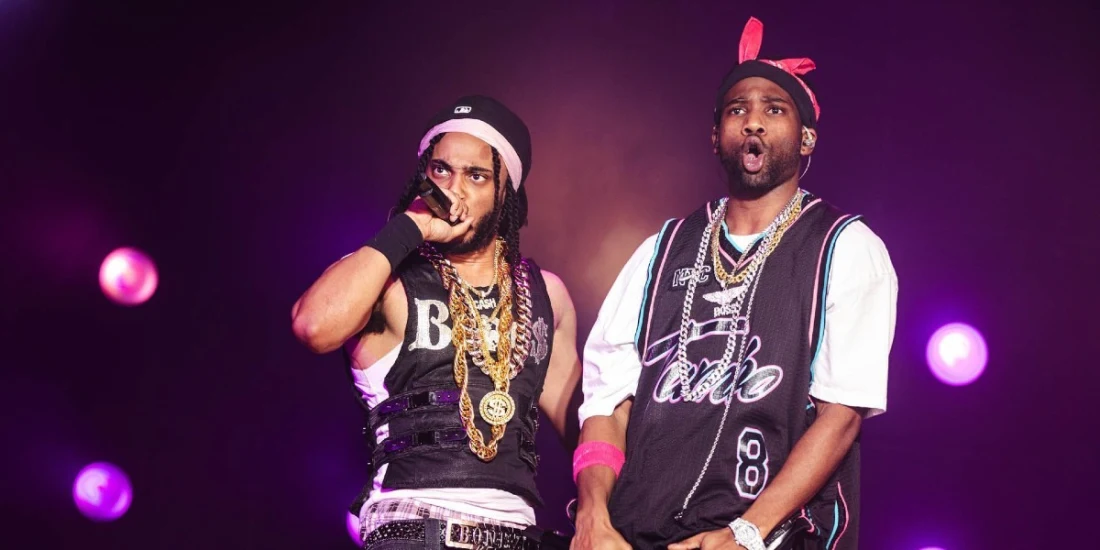

Tambo & Bones is a story about two waggish characters: a tired Tambo (W. Tré Davis) and a quarter-chasing Bones (Tyler Fauntleroy) who realize they've been written into a neverending minstrel show. Set amid "fake ass trees" and "fake ass sun," straight out of the Teletubbies playbook (by Stephanie Osin Cohen), the duo spit an act of sad lies and fluff to score quarters from a gullible audience. (Like clockwork, participants in the front row dug deep into their pockets on the night I went.) Their plan: Score enough "quarters to dollars" to get out of the show.

The character's relationship to the playwright is adversarial. "You had the possibility to dream up any world you could have and the extent of your imagination was to put us in a minstrel show?" (They find the playwright — a stuffed and lifeless likeness — in the audience and angrily drag him onto the stage for public viewing.) Harris says Tambo & Bones was conceived as he thought about his days of doing poetry slams, and how he found there was an expectation for Black artists to revisit and present trauma, often in front of largely white audiences.

The bajumbled storyline is amplified with bold lighting design by Amith Chandrashaker, along with Mextly Couzin and Dominique Fawn Hill's rags-to-riches costumes that serve as a mix of rag tags and 90s streetwear. Through every act change — each an important and necessary elevation of the plot — Tambo and Bones believe the only way out of this constant loop of oppressed caricaturism is through the extinction of white people. Whether or not that's true is not very clear after the show ends, but the plot line does offer bubbles of nervous laughter.

The real show happens when the spotlight turns to the audience. The laughter is heightened and uncomfortable throughout, many older white patrons serve stark looks of confusion, and some younger theatregoers devour the work on stage to taking in messages with a grain of salt. With that being said, Tambo & Bones's message is not immediately (or for that matter ever) clear. The play is loaded with a lot of meaningful points with piled-on distraction.

White audience members may miss the boat and simply laugh while having a grand ole good time, while Black members feel disappointed or angry with the shucking and jiving. The playwright's heart may have been in the right place, but overall the work misses the beat, and the play shortchanges its audience.

Originally published on