'The Doctor' review — Juliet Stevenson's intense performance is just what the doctor ordered

Read our four-star review of The Doctor, Robert Icke's play starring Juliet Stevenson, playing off Broadway at the Park Avenue Armory through August 19.

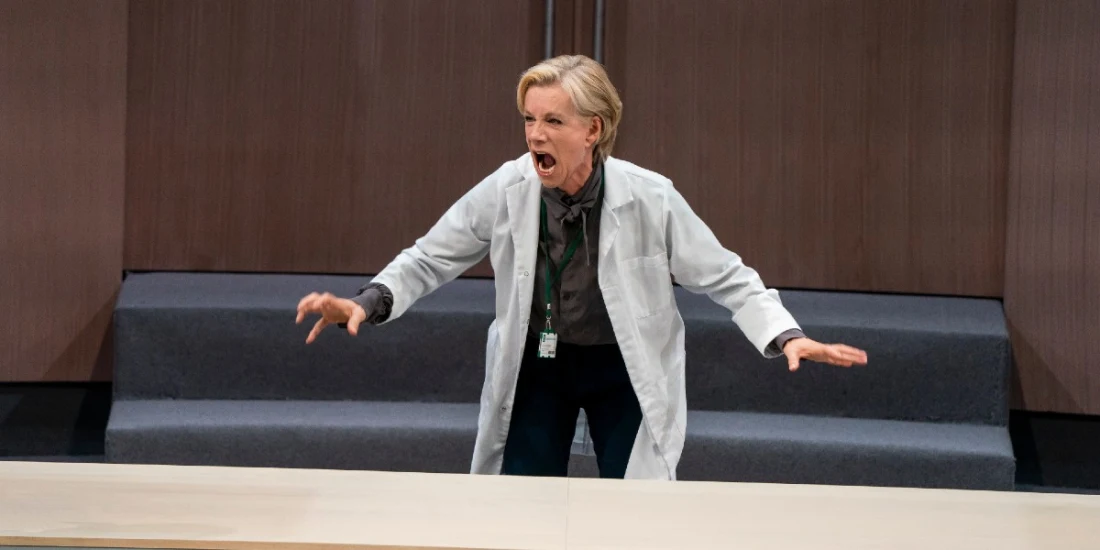

In The Doctor, English actress Juliet Stevenson barks and howls and eventually simpers as Ruth Wolff, a physician who defines her entire identity by her profession. “I didn’t get that title for Christmas,” she says. “It’s the result of quite a lot of work.”

As a doctor, Wolff moves through life with complete confidence. When it comes to every decision, she is, to quote her pet phrase repeated 10 times over the course of the play, 100% “crystal clear.”

But is she really? Writer and director Robert Icke has painstakingly constructed the play to be murky. “It’s important that the audience are never told whether the character is male or female,” he notes about Ruth’s partner in the script.

As such, several characters are cast against gender and race to keep the audience off balance and to spark thought about identity and preconceived perceptions and prejudices. It’s potentially provocative, but it’s used so much here the impact is diluted. The device takes you out of the play and into a guessing game.

Similarly, Icke juggles so many hot-topic themes – abortion, Alzheimer’s, anti-Semitism, and that’s just the A’s – the play gets diffuse. At its best, The Doctor, which is based on a 1912 play by Arthur Schnitzler, raises a straightforward, chilling point: One decision can alter the entire trajectory of a carefully constructed life.

That’s what happens to Wolff – “double-f,” she notes, to separate herself from the beast – the celebrated founding director of the Elizabeth Institute, which is bent on beating Alzheimer’s. In glimpses of her home life, we see how Wolff relates to that on a personal level. Her colleagues refer to her as BB, as in Big Bad. That nickname actually fits. Wolff does a whole lot of huffing and puffing and hollering.

That escalates when Wolff’s patient, a 14-year-old girl who develops a fatal infection after taking abortion pills, dies under her care. Exactly what a teenager is doing at a dementia institute is a glaring question. Icke covers it curtly and conveniently. “I saw her come out of the ambulance,” says Wolff.

The case gets more complicated by the minute. The patient’s parents are Catholic, and before she dies a priest arrives to administer last rites. Wolff refuses to let him into the girl’s room. She claims that she doesn’t want the patient to be upset. Push comes to shove between the doctor and the priest – and Wolff is the one who gets physical. To stir the pot further, Wolff is Jewish. It later comes out that the priest, who’s played by an actor cast against type, is Black.

The incident becomes headline news as online naysayers denounce Wolff. It’s a public relations catastrophe for the institute, which is looking to expand. Wolff and her career come under intense fire. Some colleagues support her, while others can’t defend her actions because of their faith, ethics, or aspirations to take over the institute.

The play is like an inverted onion – layers pile on. The second half of the play reviews its hot topics when the embattled Wolff appears on a TV show called Take the Debate. Panelists take on Wolff about race, religion, faith versus medicine, abortion, the right to choose, and more. The move that feels a bit contrived since Wolff wouldn’t put herself in a vulnerable position.

Icke, who brought his stagings of Hamlet and Oresteia to the Park Avenue Armory last year, underscores the story with a live drummer. It's an interesting choice, though not altogether necessary. The intense central performance by Stevenson, who throws herself truly, madly, deeply into the demanding role, needs no accompaniment.

Photo credit: Juliet Stevenson in The Doctor. (Photo by Stephanie Berger/Park Avenue Armory)

Originally published on